by Sophia Brook

Australia and the Solomon Islands – Walking the Tightrope

Digital Snapshot #18/22

16 September 2022

A potpourri of current affairs topics from Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific brought to you by KAS Australia and the Pacific. The weekly digital snapshot showcases selected media and think tank articles to provide a panorama view and analysis of the debate in these countries.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in these articles do not necessarily reflect KAS Australia’s position. Rather, they have been selected to present an overview of the various topics and perspectives which have been dominating the public and political debate in Australia and the Pacific region.

Australia’s foreign policy focus post federal election has increasingly been on repairing and enhancing its relations to partners in the Indo-Pacific region, especially in view of recent developments in the aftermath of the AUKUS announcement and its ongoing complicated relationship with China.

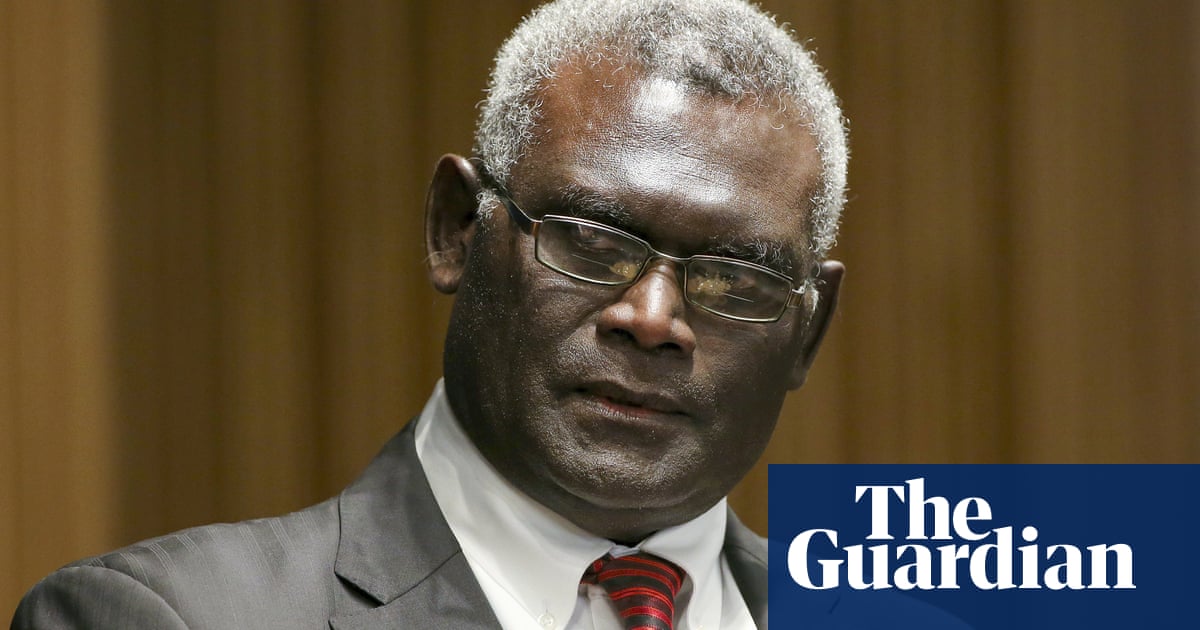

This week, the media debate returned to the ongoing issue around China’s influence in the Solomon Islands, less than 2000 kilometres distance to Australia (see Snapshot #11/22 for more background), and Solomon Islands PM Sogavare’s increasingly assertive rhetoric towards partner nations he perceives as too critical. Former Australian Liberal MP Dave Sharma recently labelled the Solomon Islands a ‘Beijing-backed autocracy in our backyard with Cuba in the Pacific’, warning that it was on a ‘deeply concerning trajectory under Sogavare’. More moderate observers, like the Lowy Institute’s research fellow in the Pacific Islands program Mihai Sora, say that the relationship between the new Australian government and the Solomon Islands started off well, but ‘remains complex’.

The latest rocky patch started in August, with the Solomon Islands announcing a moratorium on all navy ships entering its ports. This resulted in US and British vessels being turned away and, in some instances, their requests for refuelling stops simply being left unanswered. Mr Sogavare’s explanation that the moratorium was due to a new mechanism for approving and notifying stopover requests being put into place was largely viewed – particularly by the US – as yet another confirmation of his government’s moving closer to China. Meanwhile, Australian reactions were muted. ‘Ultimately, those decisions are a matter for the Solomon Islands’, Defence Minister Marles told the ABC, ‘I’m confident that if we put in the work as a nation, we will be the partner of choice for Solomon Islands and we are putting in that work.’. Sogavare later clarified that Australian and New Zealand vessels would be exempt from the ban. Keeping in mind that Australia has gifted patrol boats to the Solomon Islands in the past and is currently assisting them with building a patrol boat outpost in the western provinces, any other decision by the Sogavare government would have had a significant negative impact on bilateral cooperation between the two nations.

Following this point of tension, another, more heated argument followed last week, as an aftermath of the recent announcement by Prime Minister Sogavare that it was impossible to hold elections in 2023, due to the Solomon Islands hosting the Pacific Games that year. This would mean that the nation would not have the necessary funds required to also hold an election. A ‘Constitution (Amendment) Bill’ was tabled by the Sogavare government to postpone the general election, which was scheduled for May 2023, until 2024. As the Pacific Games are largely bankrolled by China, with Australia also committing to contribute around $17 Million, this announcement was largely held to be part of a greater trend to centralise and hold on to power for longer.

In an effort to keep the election on track, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong offered Australian funding for it. The offer was widely reported on by Australian media and ultimately resulted in PM Sogavare publicly accusing the Australian government of foreign interference. ‘This is an assault on our parliamentary democracy and is a direct interference by a foreign government into our domestic affairs.’, a statement read, ‘Solomon Islands is a sovereign country and its Parliament must not be seen to be coerced or unduly influenced by ill-timed offers that is directed to a matter before Parliament.’. Interestingly, consecutive Australian governments have supported election processes in the Solomon Islands either financially, logistically or both for the last 20 years without any issues. Foreign Minister Penny Wong stated that the offer reflected ‘Australia’s longstanding commitment’ to democracy in the Pacific. ‘We have made an offer of assistance, and it’s a matter for Solomon Islands as to whether they will respond and how they wish to respond.’.

It was then explained by the Solomon Islands that, although the offer was appreciated, the timing of its publication, coming on the eve of its parliament voting on the ‘Constitution (Amendment) Bill’, was deemed poor. Australian Opposition foreign affairs spokesman Simon Birmingham also criticised Wong’s timing, but had to concede that the offer itself was appropriate.

Regardless of the Australian funding offer, the Solomon Island government voted in favour of delaying its national elections 37 to 9. So instead of heading to the polls in 2023, the elections will now likely be held in late April 2024. In a final twist, speaking to parliament after the vote, Prime Minister Sogavare accepted Australia’s offer to fund the elections in 2024. ‘We look forward to Australia’s offer to assist us in funding the pre-requisite electoral reforms and the conduct of the national elections. They’ve offered now, so you get ready brother to fund the costs. It’s a big cost, Mr Speaker. The electoral commission needs a lot of money.’. The statement appears to be mocking the Australian government, which, so far, seems to have decided to ignore the bait.

With PM Sogavare having made worrying statements about press freedom in recent weeks and his inclination to open the door to Beijing, the Australian government needs to walk a fine line between proving itself as a reliable partner without appearing overbearing or commanding, and offering an alternative to China without compromising its own values of free speech and democratic process.