The Fiji election of 14 December 2022 was the third held under the 2013 Constitution. It resulted in a narrow victory for the opposition parties, which together obtained 29 of the 55 seats. In the Prime Ministerial vote held on Christmas Eve, People’s Alliance Party leader Sitiveni Rabuka was selected as Prime Minister by 28 votes to 27. The election brought to an end 16 years of semi-authoritarian rule by the military-backed government that assumed office in the wake of the December 2006 coup. Bainimarama’s FijiFirst Party had won the 2014 elections with 59% of the popular vote and the 2018 elections, more narrowly, with 50.02% of the nationwide vote. In December 2022, that party secured 42.6% of the vote, which was enough to make it the largest party in parliament with 26 seats, but not enough to form a government. The December 2006 coup leader and 2007-22 Prime Minister Frank (‘Voreqe’) Bainimarama became Leader of the Opposition.

Fiji is a small Pacific Island country located to the east of Australia. It has a population of around 900,000, the vast majority of whom live on the main island of Vitu Levu. It was a British colony from 1874 to 1970. Under British colonial rule, over 60,000 indentured labourers were brought from the Indian subcontinent to work in the sugar cane fields. By the 1940s, the descendants of those migrants outnumbered the indigenous population. By the 1980s, the two populations were close to parity, owing to a recovery in indigenous fertility rates. By 2007, the Fiji Indian population was down to 36.7% and the indigenous share up to 55.8%, largely due to out-migration by Fiji Indians to Australia, New Zealand or North America. Ethnic affinities have been an important basis for electoral loyalties in the past. For most of the post-independence period, there was one large party that appealed to indigenous Fijians and another large party that appealed to Fiji Indians. This was not the case in December 2022: that election was fought between two multi-ethnic parties or coalitions.

After independence, Fiji experienced three coups: in 1987, 2000 and 2006. The first, in May 1987, was a military coup that came shortly after the election of a largely Fiji Indian backed coalition. On 19 May 2000, a second coup followed the May 1999 election of another mainly Fiji Indian-backed party led by Fiji’s first ever Prime Minister of Indian descent, Mahendra Chaudhry. This time, the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) was split. The then RFMF Commander, Frank Bainimarama, led a counter coup on 29 May 2000 and abrogated the 1997 Constitution, but he handed over the reins of power to a civilian government in July 2000. On 5 December 2006, Bainimarama overthrew another elected government, but this time that government was one that had been backed at an election held eight months earlier by 80% of indigenous Fijians. Unlike its predecessors, the 2006 coup was initially depicted as a ‘clean-up campaign’ against corruption and as a military takeover designed to bring an end to ethnic discord, but there followed extensive repression of the opposition, media censorship and the abrogation of the constitution in 2009. It was on the basis of an egalitarian, meritocratic and development-oriented agenda that Bainimarama’s FijiFirst Party was able to win the 2014 and 2018 elections. Whereas the ethnic divide was the key cleavage around which parties were configured prior to the 2006 coup, at the elections of 2014, 2018 and 2022 the key cleavage was between the party that assumed office as a result of the 2006 coup (FijiFirst) and those parties opposed to that coup.

The December 2022 election, like those of 2014 and 2018, was conducted using an open list proportional representation system. The entire country was treated as a single constituency with 55 seats and a 5% threshold. The ballot paper featured only numbers, with each number representing a candidate. After the polls, ballots are counted to establish the number of seats for each party using the d’Hondt system. Once the party tallies are known, the seats secured by each party are allotted to its candidates with the highest votes. One consequence is that some candidates may be elected with lower vote tallies than others. This arose in all three of the elections since the passage of the 2013 Constitution. It was explained by a difference in campaign tactics between FijiFirst and the opposition parties and, initially in 2014, by the strong personal popularity of military commander-turned civilian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama. During those campaigns, FijiFirst emphasised Bainimarama’s personal ballot paper number whereas the opposition parties had more candidates with a strong vote at the local level. Whereas FijiFirst used a ‘rock star’ high profile party leader focussed campaign strategy, the opposition parties had a more even distribution of their votes across their candidates. Hence, many FijiFirst candidates were elected on the basis of Bainimarama’s personal vote.

After 2014, numerous electoral amendments were passed that disadvantaged the opposition, including laws to diminish the autonomy of the electoral commission, to expand the authority of the Supervisor of Elections and to require parties to cost their campaign pledges. Another amendment required women to register in the name on their birth certificates, disenfranchising many women who had hitherto been registered using their married names. After the FijiFirst election defeat in December 2022, the Supervisor of Elections, Mohammed Saneem, was suspended ahead of a disciplinary tribunal but he then resigned to avoid the proceedings.

During the 2022 election campaign, FijiFirst echoed its tactics of 2014 and 2018 by appealing for personal votes for its leaders: Bainimarama and his Attorney-General and Minister for the Economy, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum. The latter had served as de facto Prime Minister during the governments of 2014-18 and 2018-22, with Bainimarama playing a more ceremonial role, touring the country to open roads, wharves, bridges and buildings and travelling regularly overseas to attend international events, such as climate change summits. Most of FijiFirst’s ministers re-contested and were re-elected, but most of the other FijiFirst candidates were new. The FijiFirst manifesto defended the incumbent government’s achievements in protecting the country during the Covid-19 pandemic. That pandemic hit the country’s tourism industry particularly badly, with visitor arrivals falling to near to zero over 2020-21. The national airline, Fiji Airways, was driven close to bankruptcy but was bailed out by the government and then rescued by the country’s main pension fund acquiring a major stake in July 2022. By November 2022, visitor arrivals had recovered to close to pre-pandemic levels. In December, FijiFirst again acquired most of its support from Fiji Indian voters and an overwhelming majority among citizens residing in the western part of Viti Levu, Fiji’s largest island. At one campaign rally, Bainimarama told his audience that ‘my party should be in power forever because it will provide unity forever’.

Ahead of the 2022 polls, the opposition was thoroughly reconfigured. A new party, the People’s Alliance Party, was established and able to largely displace what was formerly the largest opposition party, SODELPA (the Social Democratic and Liberal Party). SODELPA was a reincarnation of the party that held office prior to the 2006 coup, when it was led by Laisenia Qarase. After serving a prison sentence for what Amnesty International has described as a politically-motivated corruption conviction, Qarase was prohibited from contesting in 2014. At the 2018 polls, SODELPA was instead led by Sitiveni Rabuka, the 1987 coup leader and 1992-99 Prime Minister. After the 2018 election defeat, a fractious leadership contest within SODELPA led to Rabuka being replaced as party leader by Viliame Gavoka, a former Chief Executive at the Fiji Visitors Bureau. Rabuka responded by resigning both as an MP and SODELPA member and by commencing preparations ahead of the launch of his People’s Alliance Party.

Half of SODELPA’s MPs defected to the People’s Alliance before the 2022 election, including traditional chief of Cakaudrove province, Tui Cakau Ratu Naiqama Lalabalavu and trade union rights and anti-poverty activist Lynda Tabuya. The People’s Alliance was also able to attract numerous high profile new candidates, including Manoa Kamikamica (now one of three deputy prime ministers). SODELPA was left with only 5% of the national vote, as compared to the People’s Alliance Party’s 35.8%. Whereas SODELPA remained an almost entirely indigenous-backed party, the People’s Alliance was able to attract some minority support from within the Fiji Indian community, as seen in the election of Fiji Indian businessman Charan Jeath Singh drawing on a sizable personal vote on the country’s second largest island, Vanua Levu. The People’s Alliance secured a majority of the votes from Vanua Levu and most of the outer islands and, critically, was neck and neck with FijiFirst in the densely populated Central Division, which covers the southeastern part of Viti Levu. When single-member electorates were used (1972-2006), district design discriminated in favour of the sparsely populated rural areas. By now treating the entire country as a single district, Fiji has ended the former bias against the more densely populated urban areas.

Rabuka established a coalition with the National Federation Party (NFP), echoing the close alliance he had forged with that party under the leadership of Jai Ram Reddy in the late 1990s. In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the NFP had been a predominantly Fiji Indian-backed party. From the 2014 election onwards, it cultivated a more multi-ethnic appeal. Under the leadership of former economics professor Biman Prasad, and with former military officer and permanent secretary Pio Tikoduadua serving as party president, the party was able to lift its share of the vote from 7.4 in 2018 to 8.9% in 2022, and its number of seats from three to five. The party released no manifesto ahead of the 2018 polls, owing to fears of potentially violating the government’s strict electoral amendments relating to costing manifesto commitments. NFP’s leaders, like those of the People’s Alliance, were regularly brought in for police ‘questioning’ during the campaign. Three of SODELPA’s sitting MPs were unable to contest because they were serving prison sentences in December 2018, in each case for claiming allowances by stating that their main place of residence was their home village while they were residing in the capital, Suva.

Turnout across the whole of Fiji was 67.8% of registered voters, down from the 70.9% in 2018. Use of designated polling stations lowered turnout, as did delaying the election until mid-December, close to Christmas and in the midst of Fiji’s rainy season.

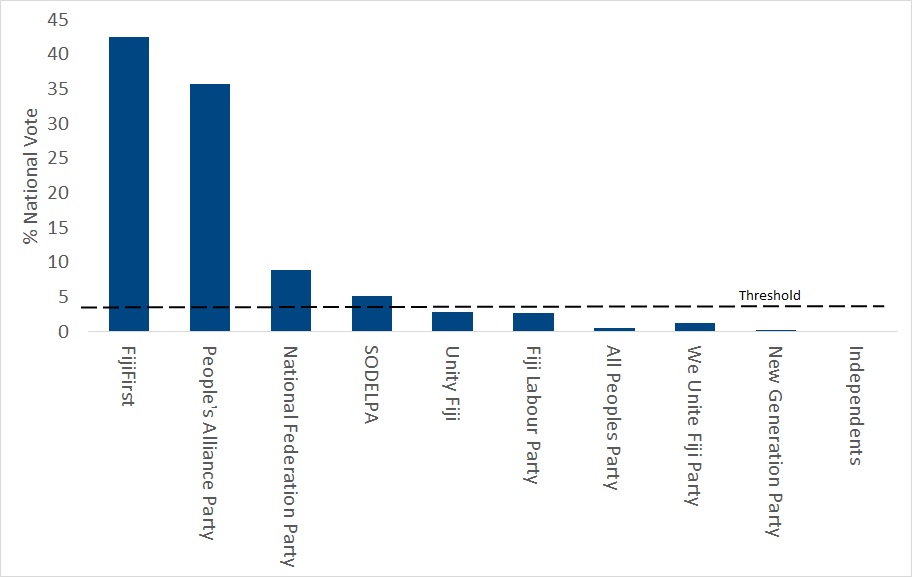

Figure 1: Results of the 14 December 2022 Election

The results of the December 2022 election left Fiji in a delicately balanced situation. FijiFirst had 26 seats in the 55-member parliament. Together, the People’s Alliance (21) and the National Federation Party (5) also had 26 seats. During the initial provisional ballot count, it looked as if all of the other parties would fall below the 5% threshold (see Figure 1). If so, FijiFirst would have won the election. Yet at the final count, SODELPA narrowly crossed the threshold with 5.1% of the vote, giving it the decisive three seats in parliament. Similar to the People’s Alliance, SODELPA prioritised indigenous rights issues. It was deeply opposed to FijiFirst policies, such as the 2012 abolition of the country’s Great Council of Chiefs, formerly the peak body in the country’s indigenous order. On the other hand, there was much bad blood between SODELPA and the People’s Alliance owing to the rancorous 2020 leadership contest, the defection of so many SODELPA MPs, and the People’s Alliance campaign tactic of insisting that a vote for the smaller parties was a ‘wasted vote’. In addition, SODELPA leader Viliame Gavoka is father-in-law to Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, the FijiFirst General Secretary and right-hand man to Bainimarama, which encouraged many to suspect that family ties might encourage support for a coalition with FijiFirst. Yet at the initial meeting of the SODELPA Management Board to decide whether the party would go into coalition with FijiFirst or with the other opposition parties, the party came down 16:14 in favour of joining the opposition coalition. Joyous celebrations by opposition supporters ensued.

The next day, however, party General Secretary Lenaitasi Duru claimed that the Management Board decision had not been reached in accordance with SODELPA’s constitution. The Supervisor of Elections and the Attorney General agreed. At this precarious juncture, the Police Commissioner, Sitiveni Qiliho, himself a former military officer and strong Bainimarama loyalist, claimed that ‘stoning incidents’ were occurring that were targeting ‘minority groups’ (i.e., Fiji Indians) and called out the army. Many feared that this was being used as a pretext for yet another coup. The precarious security situation was used to place the SODELPA Management Board under duress as they re-convened to again decide on their coalition partner. For the second such meeting, five of those who had voted at the first Management Board meeting were ruled ineligible. Again, FijiFirst and the opposition party leaders initially attended the meeting offering ministerial portfolios, board memberships and other inducements to SODELPA. On 23 December, SODELPA again decided in favour of a coalition with the opposition parties, this time by 13 votes to 12. The Military Commander, Jone Kalouniwai, who had promised in early December to honour the election result, stood by his word. Only a small military deployment was ordered to support the heavily policed re-run of the SODELPA gathering.

After Rabuka’s election as Prime Minister on Christmas Eve by 28 to 27 votes, Bainimarama told the media: ‘this is democracy, this is my legacy: the 2013 Constitution’. Yet the security situation remained fraught. In two FijiFirst press conferences in early January, Bainimarama delivered blistering attacks on the new Government, accusing it of breaching the 2013 Constitution and calling on constitutional office-holders, including the Police Commissioner and Commissioner of Prisons, to refuse appeals for their resignation. Military Commander Jone Kalouniwai issued a statement warning the government against breaching the separation of powers, but his officers remained in the barracks. He also repeatedly appeared alongside government ministers, including both Rabuka and Home Affairs Minister Pio Tikoduadua, so as to reassure the nation that the military was behind the new Government. Appeals were also made by Bainimarama and Sayed-Khaiyum to the President, Ratu Wiliame Katonivere, who had until then been closely aligned with FijiFirst, to step in to pronounce the new Government in breach of the constitution. He refused. On 16 February, Bainimarama delivered a speech in parliament attacking the President and appealing to the rank and file in the military to protect the 2013 Constitution. He was suspended for three years for breaching Standing Orders. If the new Government survives, the December 2022 election will be Fiji’s first ever enduring transition of power since independence. Changes in government in 1987, 2000 and 2006 were each followed by coups, the first within a month, the second a year later and the third after eight months. Fiji is therefore not out of the woods yet. The fact that powerful constitutional office-holders, particularly the President and the Military Commander, have sided with the Rabuka-led government augers well, but some of those in the military continue to defend the 2006 coup as if it were a ‘noble’ act by the RFMF. The 2013 Constitution remains a major issue. It was imposed on the people of Fiji. No elected representatives were responsible for its formulation. It was not passed by way of a referendum. Yet it cannot be amended without the support of 75% of MPs followed by the endorsement of 75% of all registered voters in a referendum – an extraordinarily high threshold. Given continuing military support for the 2013 Constitution, the new Government is well advised to tread cautiously. There is no need for hurry. Nothing in the 2013 Constitution prohibits the initiation of a review process, at the appropriate time. Deliberation is in any case necessary on a suitable replacement, which will require extensive consultation. Until then, the Fiji government is advised to cement its own position, to deal firmly with spoilers of the transition but not to pursue vendettas against all of those who accommodated with the FijiFirst governments. The early signs are promising, but the passage of time will bring fresh challenges.

Endnotes

- The expected result had been 29 votes to 26, but one unidentified member of one of the three coalesced opposition parties defected in the secret ballot for the prime ministerial post

- Rule was ‘semi-authoritarian’ in the sense that elections were held, but not on a level playing field, and there was extensive media censorship and police repression directed against opposition leaders. For further details regarding ‘semi-authoritarian’ and ‘competitive authoritarian’ regimes, see Howard, Mark Morjé & Roessler, Philip, 2006. ‘Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes, American Journal of Political Science, 50, (2), 2006, pp365-8; Levitsky, Stephen & Way, Lucian. 2002. ‘The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism’, Journal of Democracy, 13, (2), pp51-65; Morse, Y., 2012. ‘The Era of Electoral Authoritarianism’, World Politics, 64, (1), pp161-98

- Fiji Bureau of Statistics, 2007 census of Population and Housing, available https://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/

- There were some exceptions when schisms emerged among Fiji Indian voters (the ‘dove’ and ‘flower’ factions of September 1977, and the two party competition between the Fiji Labour Party and National Federation Party in 1992 and 1994). The main indigenous party before the 1987 coup was Ratu Mara’s Alliance Party. After the 1987 coup, it was the Soqosoqo ni Lewenivanua ni Taukei (SVT). After the 2000 coup, it was the Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua (SDL). All of these dominant Fijian parties faced smaller rival parties, often regional parties based in specific parts of the country. In 1999, the SVT was the largest Fijian party in terms of vote share (38% of the indigenous communal vote), but not in seat numbers (the SVT secured only eight seats, while the Fijian Association Party obtained eleven). For an explanation of how the alternative vote electoral system contributed to this outcome, see Jon Fraenkel, ‘The Alternative Vote System in Fiji; Electoral Engineering or Ballot-Rigging?’, Journal of Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 39, (2), 2001, pp1-31.

- Bainimarama abrogated the 1997 Constitution on 29 May 2000, but the Court of Appeal resurrected that Constitution in the Chandrika Prasad case of March 2001

- Islands Business, ‘Why we are bailing out Fiji Airways’, 2 June 2022

- Fiji Times, 1 December 2022

- ‘Fiji’s former Prime Minister imprisoned on politically motivated charges’, Amnesty International Public Statement, 8 August 2012

- The immunities given to the coup perpetrators of 1987 and 2006 cannot even be changed by a referendum