In November 2025, Tonga witnessed its fifth election since sweeping reforms introduced a majority popularly elected parliament and, ostensibly, ended the King’s control over the selection of government.

Yet in the wake of that election, the new Prime Minister is a noble, the former Speaker Lord Fakafanua, who on 15 December 2025 defeated the outgoing incumbent, ‘Aisake Eke, by 16 votes to 10. That outcome is, in one sense, a sign of the enduring powers of the nobility, despite the democratic reforms of 2010. More importantly, it signals a further step in the reassertion of monarchic authority by King Tupou VI, after a troubled 2021-25 term of parliament during which key areas of government – defence and foreign affairs – were wrestled back from the control of elected representatives. The limits of the reforms of 2010 have now been starkly exposed.

Tonga went to the polls on 20 November 2025 to re-elect its 26-member legislative assembly. The country has 149 islands spread across a total exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of around 700,000 square kilometres. Three-quarters of its 100,000 people live on the main island of Tongatapu, where the capital Nuku’alofa is located.

Although the 2010 reforms expanded the number of popularly elected representatives from 9 to 17, they left nine representatives selected by the holders of the country’s 33 recognised hereditary noble titles. On the campaign trail, one of their number – Lord Vaea, the King’s brother-in-law, claimed that it was time for the nobility to resume their historic leadership role in Tonga. He has had his way. Not only is the Prime Minister now a noble, but so too are the Speaker and Deputy Speaker. The Crown Prince, Tupouto‘a ‘Ulukalala, has again been appointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister for his Majesty’s Armed Forces.

The pro-democracy movement, which won sweeping victories in the elections of the 1990s and 2000s, no longer exists as a unified force. Since the death in office of veteran democracy activist and 2014-19 Prime Minister ‘Akilisi Pōhiva, what was once called the Democratic Party of the Friendly Islands has fragmented. On his deathbed in 2019, Pōhiva appointed a politician of Mormon faith as his successor, but his mostly Methodist cabinet ministers rejected that choice. Since then, the pro-democracy politicians have been plagued by personal rivalries, opening the door to the noble resurgence. Only four or five of the freshly elected MPs are known supporters of democracy. Only one woman was elected. She defeated the only female MP in the outgoing parliament. The new Prime Minister, who at 40 years of age is Tonga’s youngest ever, is the holder of one of the 33 noble titles, and he owns estates on the three main islands groups of Tonga: Tongatapu, Ha’apai and Vava’u. He is the King’s nephew and the Crown Prince’s brother-in-law. Of the 16 MPs who backed Lord Fakafanua in the secret ballot, ten were People’s Representatives, says Pōhiva’s daughter Teisa Pōhiva, who called this a ‘sad day for Tonga’s democratic reforms’.

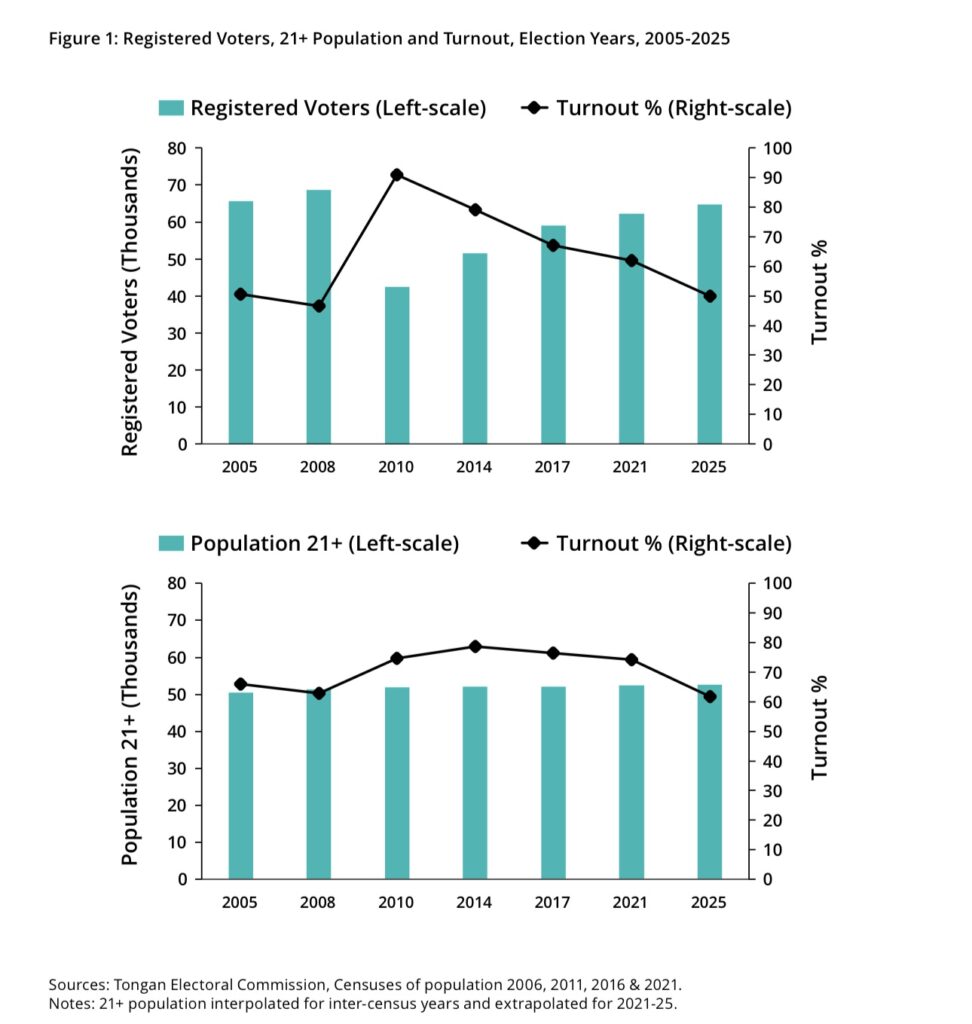

Turnout was well down on previous elections. Less than half of Tonga’s 63,484 registered voters cast ballots in 2025. According to the Tongan Electoral Commission (TEC) figures, turnout has declined at every election since the 2010 reforms. It peaked at over 90% in 2010, but fell continuously over 2014, 2017, 2021 and 2025. Figures from before 2010 are not comparable with the later figures because of the shift from multi-member districts (in which eligible citizens had multiple votes) to first-past-the- post (with a single vote).

Part of the reason for the decline may be an inflation in the number of registered voters. The left-hand side of Figure 1 shows the official turnout data and, in the columns, an increase in the number of registered voters from just under 42,400 in 2010 to 64,707 in 2025. The right-hand side chart shows turnout instead relative to the 21+ voting age population using census figures, which was fairly flat over the 2005-2025 period. Some decline in turnout remains visible after 2014, but it is not as acute as is suggested by the TEC figures. The census data suggests that there were just over 52,000 eligible voters in Tonga in 2025, but there are close to 65,000 on the electoral register. The discrepancy is likely due to the large numbers of Tongans who have migrated overseas. The Electoral Act does not prohibit‘ a Tongan subject who is not resident in Tonga’ from remaining on the electoral register. Yet Tongans overseas cannot vote unless they return home.

Since the mid-19th century, Tonga has been a constitutional monarchy, or what legal scholar Guy Powles once called ‘a constitution under a monarchy’. Its 1875 foundational law formalised the King’s control over cabinet, whose ministers sat unelected in parliament alongside equal numbers of nobles and popularly elected People’s Representatives. The reforms in 2010 saw the Monarch give up the right to choose both the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The amended Constitution gives Cabinet ‘executive authority’ and makes Cabinet ‘collectively responsible to the legislative assembly’, but it also defines the term ‘executive authority’ to ‘exclude […] all powers vested in the King or the King in Council, whether by this Constitution, or any Act of the Legislative Assembly, any subordinate legislation, and Royal Prerogatives’. It left the King not only with powers of dissolution of parliament and with a veto over legislation, but also over appointments to the judiciary. Even the government’s own legal advisor, the Attorney-General, remained royally appointed. The 2014 Pursglove report concluded that the amended Constitution ‘can lay claim to being the most poorly structured and drafted Constitution of any Country in the Commonwealth.

Since the current Monarch ascended to the throne in 2012, even ceremonial powers have been hardened. The King and his Privy Council chose Tonga’s anti-corruption commissioner in 2024, its police commissioner in May 2025, and the chairman of its Electoral Commission in 2016. The Privy Council, where the King once sat with ministers, survived after the 2010 transition but now separated from cabinet, as a shadowy institution of dual power which leaves functionaries in the ministries uncertain of lines of executive authority. As Pursglove warned, ‘while the Ministry of Justice remains accountable to the people through Parliament, the Office of the Lord Chancellor and the Office of the Attorney-General are not publicly accountable and answer only to the King in Privy Council. This is contrary to the democratic principles upon which the new Constitution was founded’.

Tonga’s nobles are sometimes compared to European feudal lords or a landed aristocracy, but in fact they are beholden to the King. In the 19th century, King Tupou I defeated the rival dynasties of the Tu’iTonga and Tu’i Ha’atakulaua and abolished the old noble titles replacing them with a smaller group of hand-picked nobles whose loyalty is to the Tupou dynasty. What Lord Vaea sees as a resurgence of aristocratic leadership is therefore really a reassertion of royal power.

This is not the first time that a noble has assumed the prime ministerial portfolio since the constitutional amendments 15 years ago. Owing to the reconfiguration of parliament in 2010, popularly elected MPs had the potential to obtain control over government, … if only they could remain united. They did not. Despite the then King, George Tupou V, indicating a preference for a peoples’ representative to head the government, a noble Lord Tu’ivakanō, defeated Pōhiva in the first post-reform prime ministerial election by 14 votes to 12.

After he acceded to the throne in 2012, King Tupou VI refused to accept a merely ceremonial figurehead role. Pōhiva managed to become Prime Minister in 2014 by 15 votes to 11 with all of the nine noble MPs arrayed against him. The King subsequently pushed back against the democratic reforms introduced by his eccentric elder brother, particularly with regards to powers to ratify international treaties. In 2017, angered by his troubled relationship with the Prime Minister who he accused of ‘trespassing’ on royal authority, the King prematurely dissolved parliament. He was acting on the advice of the Speaker, Lord Tu’ivakano, who highlighted alleged government encroachment on royal prerogatives. It proved a rude awakening. Pōhiva’s Democratic Party was returned with an increased majority at the November 2017 polls, acquiring 14 of the 17 popularly elected posts. The defiant Pōhiva was triumphantly re-elected as Prime Minister, but he soon fell ill and died in office in September 2019.

Ever since, at least until now, Tonga’s Prime Ministers have been Peoples’ Representatives, but they have been required to pay ever more homage to the palace. After Pōhiva’s death, the former Minister of Finance Pōhiva Tu’i’onetoa assumed the prime ministerial portfolio, but he became a vigorous opponent of the pro-democracy faction, accusing them of seeking to dethrone the King. The reassertion of royal powers has been particularly striking feature of the 2021-25 parliamentary term. In the wake of the 2021 general election, Huakavameliku Siaosi Sovaleni was appointed as Prime Minister, this time with majority backing from the popularly elected MPs and with his main rival, former finance minister ‘Aisake Eke, aligned with the nobles bloc.

Sovaleni’s relations with the King soon deteriorated. In February 2024, King Tupou VI announced that he was withdrawing ‘confidence and consent’ from the minister of foreign affairs and the minister of defence, leading the elected government to spend the rest of that year trying in vain to heal the rift with the palace. Sovaleni resigned as Prime Minister in December 2024 to avoid being ousted in a no-confidence vote, which had the backing of the King. He was replaced by the obsequious ‘Aisake Eke, who managed to cultivate closer relations with the palace than his predecessor. It was he who initially appointed the King’s son, Crown Prince Tupouto‘a ‘Ulukalala, as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Defence and passed legislation to transform the Ministry of Foreign Affairs into ‘his Majesty’s Diplomatic Service’. This was apparently not enough to earn him the King’s favour to serve another term.

The new government will face challenges both on the economic and political fronts. Tonga’s economy relies heavily on remittances from migrants overseas, which are equivalent to around 44% of gross domestic product, and which held up strongly during the covid-19 pandemic.8 But these are dependent on continued outward migration, with implications for the domestic economy. Tonga owes China US$120 million, equivalent to around a quarter of annual gross domestic product. Having discharged little of that debt since the Chinese loans were first taken out in 2008, repayments have ballooned to around $US20 million per annum in 2024-25, more than the island kingdom spends on health services.9 To obtain funds to sustain social services, government has become even more reliant on foreign aid.

The Lord Fakafanua-led government is on the lookout for lucrative new sources of income from overseas, such as citizenship-by-investment schemes or passport sales. In the 1980s and 1990s, royal-appointed governments lost large sums of money in corruption scandals associated with these secretly approved schemes.10 It was a reaction to the lack of accountability and transparency under those governments that initially sparked Tonga’s democracy movement. Tonga’s long-suffering citizens may be faced with the uncomfortable choice of either tolerating similar indiscretions or rebuilding that movement.