1. Introduction & Current Context

The international trade regime was a sea of tranquillity for a long time. It was the domain of trade economists and trade lawyers, tucked away at the World Trade Organization (WTO)1 on the shores of Lake Geneva. The trade regime as it has developed is being undermined by the twin forces of geo-political confrontation and geo-economic fragmentation.

Examples for how trade is being utilised as a new battlefield abound: the curtailment or cancellation of energy deliveries by Russia to European countries, the initiation of trade sanctions by China against various products from Australia, and the trade war between China and the United States (US).

2. Weaponised Trade: A New Concept

a. How Did We Get Here?

The global and regional trade environment was largely immune from the monumental political upheaval following the fall of the Iron Curtain and was able to operate in what many trade insiders thought was “clinical isolation2” from everyday politics3. During the heyday of international cooperation, lasting just over a decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall until the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the world witnessed increased efforts at creating institutions that were designed to no longer just coordinate international affairs but to lead towards a more cooperative approach. 4

One of the outcomes of this new “Weltinnenpolitik” (roughly translatable as “global domestic governance”)5 was the creation of the WTO in 1995 which succeeded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947.6 Building on the latter, the WTO provided an institutional framework for creating and enforcing global trade rules, including a strong judicial enforcement mechanism.7 The WTO extended subject matter coverage of the GATT era well beyond the regulation of goods. It also included services and intellectual property rights and, moreover, provided far more detailed rules in a variety of areas such as subsidies and dumping, standards, as well as health and government procurement. Some of the key purposes of the GATT / WTO frameworks are to foster stable and predictable trading relations, and to prevent the unilateral, discriminatory trade actions that could fuel political hostility.8 Such measures were some of the major drivers that have traditionally led to widespread conflict.

Since then, the world has changed dramatically: the unipolar moment in which the US found itself as the lone superpower (though not the end of history as some portrayed it) has made way for an era of political and economic uncertainty. Among the most notable features are more complex international relations, the ascendance of China as a global power and the emergence of different narratives of what institutions such as the WTO are supposed to do.

b. The Concept of Weaponised Trade

Weaponised Trade is a concept that has been used by different stakeholders in a range of ways. The lack of a definition has made this concept susceptible to advancing political objectives. Misdiagnosing Weaponised Trade and overstating its incidence can be problematic insofar as it heightens the perceptions of conflict and exacerbates international tensions.

Properly understood, Weaponised Trade is the manipulation of existing trade relations to advance (geo) political objectives.9 This definition contains important elements which are worth expanding upon.

(1) Externally Oriented

Weaponised Trade is deployed to change a target government’s behaviour in potentially unrelated policy arenas. It is thus primarily externally-oriented and offensive in nature. The goal of Weaponised Trade is to coerce another government to change its behaviour or simply punish it. Defining measures as either offensive or defensive can sometimes be difficult not the least because, at times, the answer lies in the eyes of the beholder.

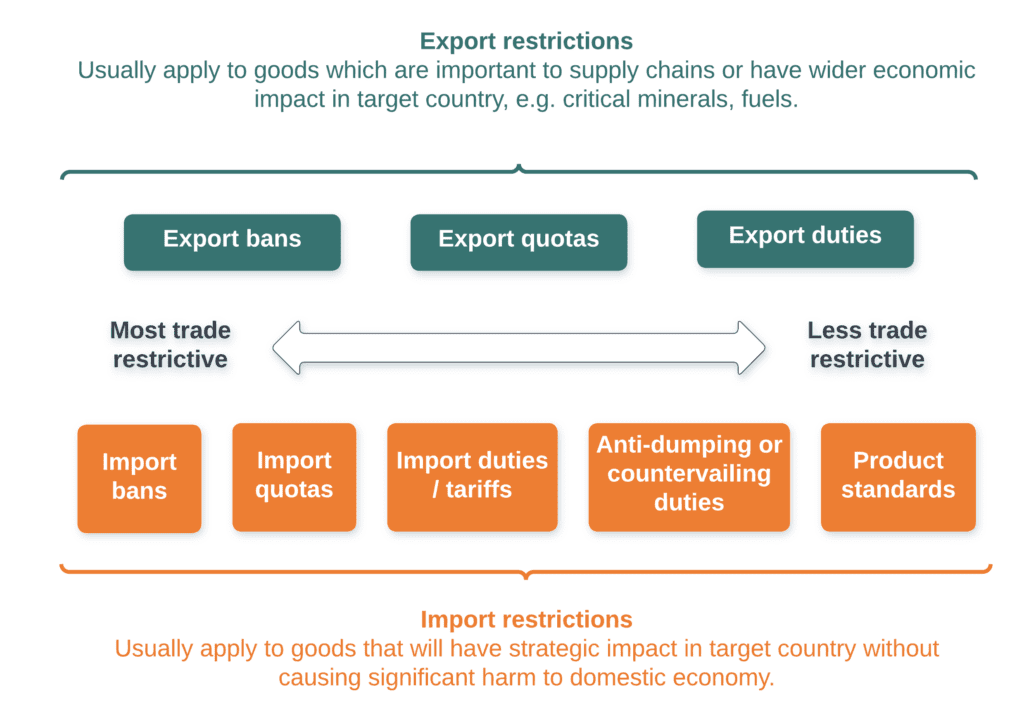

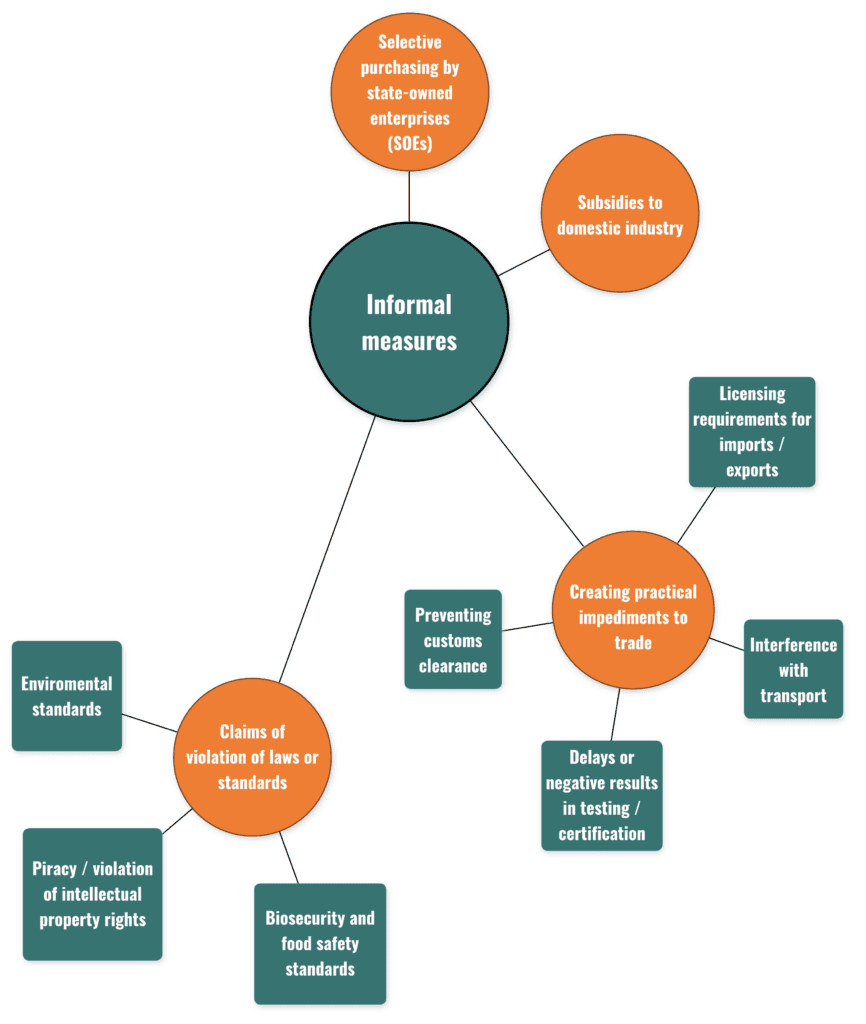

(2)Formal and Informal Measures

Weaponised Trade encompasses formal and informal measures. The latter are difficult to diagnose, and aggressors often deny that they are engaging in offensive actions claiming a veneer of legal plausibility. These measures are often carried out not only by governments but also by private actors. On the offensive side, private actors may act as a substitute for governments which leads to notoriously difficult questions of legal attributability. Commercial fishing fleets are typically private actors, but they can be enlisted to help advance state objectives by undertaking commercial activities in disputed territories. On the defensive side, while Weaponised Trade measures are primarily aimed at the target government to induce a change in behaviour, they often have direct impact on businesses and consumers.

(3) A Legal and Political Grey Zone

Weaponised Trade is distinct from regular commercial and/or trade policy issues. Some trade-related activities might disadvantage private players but simply constitute ordinary competitive commercial relations. Weaponised Trade measures on the other hand are properly characterised as a security issue: they are motivated by geostrategic objectives and can have serious geostrategic consequences.

From a legal perspective, Weaponised Trade measures fall into grey zones. They fall outside the boundaries of the acceptable use of trade for security purposes and raise security concerns because they bypass international law and because countries unilaterally apply economic mechanisms as a form of political pressure. Since some Weaponised Trade measures cannot be challenged legally, they undermine the existing systems of economic and security governance.

Properly delineated, Weaponised Trade allows for an accurate analysis of predatory economic activity. In an economically interdependent world, some governments may seek to manipulate trade relations to intentionally harm other countries and advance broader geostrategic objectives. Governments should be aware of the security challenges posed by Weaponised Trade measures and be cognisant of the range of diplomatic and policy responses it may trigger.

c. Increasing Use of Weaponised Trade

Over the last decade the use of Weaponised Trade measures has become more widespread.10 While there were occasional instances of similar measures being taken prior to 2010, they were far more discreet in nature.

- Early Example: European Union against United States in 2002

One example was the imposition of 30% tariffs on steel imports to protect domestic producers against low-cost imports in 2002 by then-US President George W Bush.11 These measures were targeted to mollify the powerful domestic steel industry, yet at the same time caused harm to downstream producers such as carmakers. This resulted in the then-European Communities (now the EU) imposing tariffs on specific US products (including iconic brands such as Harley Davidson and Tropicana, as well as recreational guns and ammunition, textiles and steel products) from certain US states to ‘leverage a change of decision’.12 The products were strategically selected and sanctions were aimed at swing states in the upcoming US election that the Republicans needed to carry to retain the House of Representatives, namely Florida, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.13 An analysis of the tariffs in the early 2000s found that 200,000 workers in the US manufacturing industries lost their jobs due to the tariffs.14

2. Recent Example I: China – United States

In early 2018, then-US President Donald Trump imposed import tariffs on China amounting to USD34 billion. These measures were put in place on the one hand in an attempt to retain manufacturing jobs in the US, but also as a response to the direct competition of China as an emerging economic superpower. The US imposed 25% tariffs on all steel imports, 30% tariffs on all solar panel imports, 50% tariffs on all washing machine imports and 10% tariffs on all aluminium imports.15 The then- President Trump relied on Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, which permits the President to impose tariffs on national security grounds.16 In March 2018, Trump used Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to justify tariffs on certain Chinese products, such as medical devices, satellites, aircraft parts and weapons, valued at USD 50-60 billion.17 These measures were justified as a response to Chinese intellectual property measures and investment that “impaired the interest of the USA”.18 China responded in April 2018 by imposing its own tariffs on US products, namely aluminium, cars, pork and soy beans.19

The latest iteration of the recurring and escalating rounds of trade measures was the imposition of new export controls concerning artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductor technologies to China.20 Under these new restrictions, US-based computer chip designers are no longer allowed to export high-end chips (defined as being smaller than 14nm) to China.

These measures are designed to set up chokepoints to set Chinese computer chip manufacturers back decades as they no longer have access to either the chips themselves or the design for these chips.21 These measures are strategic as well as offensive in nature and geared towards inducing change in the way that the Chinese Government acts with respect to gaining access to advance chip technology, thus falling squarely within the realm of Weaponised Trade.

3. Recent Example II: The Impact on Australia and Pacific Islands

Australia has been a prominent target of Weaponised Trade measures. In the years leading up to 2020, political tensions between China and Australia had been rising. Among the reasons for this development were Australia’s informal decision to ban Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE from participating in the construction of Australia’s 5G infrastructure; its call for an independent enquiry into the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan; and its criticism of the human rights situations in Hong Kong and in Xinjiang.22

In May 2020, China imposed 80% tariffs on imports of Australian barley and unofficial import restrictions on other Australian products such as beef, cotton, timber and lobster. These measures were justified by claims of breaching health standards for trade of those products.23 In June 2020, China again imposed official tariffs of up to 218% on Australian wine imports as the result of an anti- dumping investigation.24 Later in 2020, Australian coal was left waiting at Chinese ports, following unofficial orders to not process Australian coal through customs due to environmental concerns.25

One commodity that remained excluded from Chinese measures was iron ore, arguably because of China’s continued reliance on Australian iron ore.26 In 2020, Australian total exports to China reached AUD 145.2 billion, just 2% lower than the record high set in 2019.27 Producers for other products were able to explore other export markets, such as barley, beef and coal.28 The impact on the lobster and wine industries were far more detrimental.29

https://twitter.com/ErykBagshaw/status/1328983898911457280/photo/1

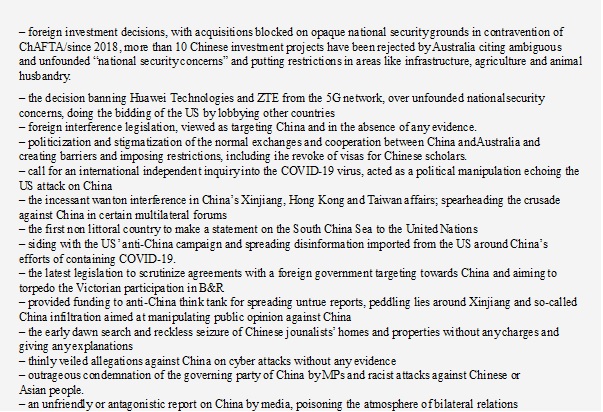

In November 2020, China’s Embassy in Canberra outlined a list of 14 grievances against Australia.30 They range from restricting China’s foreign investment in Australia on unfounded national security grounds; interference in China’s dealings with Taiwan and Hong Kong; banning Huawei and ZTE from Australia’s 5G infrastructure development; calls for an independent investigation into the COVID-19 virus; ‘doing the bidding of the US’; and a generally hostile environment created by Australian politicians and media outlets.

While there might have been some ambiguity over China’s motives in the initial phases of its measures against Australia,31 it appears now clear that China was employing rapprochement,32 Trade against Australia. It targeted industries in different Australian states and especially the politically powerful farming and commodities industries, in the hope of swaying government policy. In the end, the measures had surprisingly little impact. The Liberal Government remained steadfast in its policy settings, and it was only after a change in government in Australia that the relationship between the two countries has started to reset. Despite the beginning of a rapprochement, there is a long way to go to mend affairs and a full return to the status quo ante is unlikely. A recent meeting between Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Chinese President Xi Jinping is only a starting point for what can be expected to be protracted negotiations.33 Perhaps most tellingly, the Australian population increasingly views China to be more of a security threat than an economic partner,34 although the causes of this change in perceptions are not clear.35

While not the target of Weaponised Trade measures, Pacific Islands are often caught in the proverbial middle. The Pacific is seen by both China and the US, but also Australia and to a lesser extent New Zealand as an important strategic geographic area. Rather than being exposed to Weaponised Trade measures, the countries of the Pacific are often the subject of what could be termed “Weaponised Aid”, ie when donor governments place conditions on or (threaten to) withdraw aid to exert political pressure.36

4. Recent Example III: Europe and Weaponised Trade

Europe has not been immune to Weaponised Trade measures. The EU and European countries have been the target of Weaponised Trade on several occasions. The war against Ukraine – starting in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and returning to public consciousness in early 2022 with yet another Russian attack on Ukraine – serves as a potent reminder of the power of the impact Weaponised Trade can have.

Prior to the renewed military invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in February 2022, Russia had weaponised its energy supplies to coerce Ukraine. The country repeatedly threatened to throttle or withhold gas exports to Ukraine or gas exports transiting Ukraine to exert political influence over the Ukrainian Government.37 This was particularly the case as Ukraine signed its Association Agreement with the EU in 2014, taking an important step in the process of reorienting the country towards the EU and potentially future EU membership.38

Similarly, Russia used the dependence of a number of EU countries on Russian energy supplies in attempt to change the position of these countries’ governments regarding the war in Ukraine. Shortly after fighting erupted again in February 2022 and throughout the year, Russia has curtailed or discontinued gas deliveries – ostensibly to change the sentiment in the population of these countries regarding Russia.39 Russia’s actions have greatly contributed to an increase in energy prices in Europe and beyond.40 European countries have reacted by increasing storage capacities for gas, looking for alternate suppliers, and accelerating the transition to renewable energies. At the time of writing, it is unclear whether the unity that has characterised EU member states (and their populations) in response to Russia’s aggression41 will remain intact.

Another example of Weaponised Trade concerns Chinese trade measures against Lithuania, following the opening of a Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital in July 2021.42 China imposed informal, ad hoc measures against Lithuania in August 2021, interfering in the transport of goods between the countries, the removal of Lithuanian goods from customs clearance and pressuring EU companies to remove Lithuanian imports from their supply chains when exporting to China. The EU subsequently requested WTO consultations – a precursor to legal WTO proceedings – with China, on 27 January 2022, alleging inconsistencies with the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), GATT 1994, the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), China’s Protocol of Accession and the Agreement on Trade Facilitation (TFA).43

5. Possible Responses to Weaponised Trade

The concept of Weaponised Trade is a useful concept within the current global geopolitical environment. The existing literature has not clearly defined the consequences of Weaponised Trade.44 Understanding the consequences of Weaponised Trade and how the concept has evolved in recent years helps governments to develop new and strengthen existing strategies to mitigate the effects and potentially prevent future attempts to use trade as a potent weapon.

Because Weaponised Trade comes in a range of guises, there is no “one size fits all” response to the challenge. Governments have responded to instances of Weaponised Trade through various means. The USA and China have responded rather aggressively to Weaponised Trade with further Weaponised Trade measures. Middle powers such as Korea and Australia have deemed it more fruitful to respond with more defensive measures, seeking to reduce their trade dependence on China by diversifying their import and export markets. Some countries have commenced proceedings at the WTO.

COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine have exposed the vulnerability of supply chains and have shown the impact of their disruption on governments but also people’s lives. Governments have responded by attempting to re-shore or “friendshore” goods and services that have for a long time been taken for granted and are now seen as critical in times of crisis. These include pharmaceuticals, personal protective equipment, gas as well as precursor materials such as agricultural production chemicals and rare earths.

Given recent developments, these are rational responses by government actors. There is however a real risk that the already existing siloing of international relations in general, and international economic relations in particular, will continue to accelerate.45 This will have detrimental consequences not only for international relations but also the everyday lives of people around the world.

- https://www.wto.org/

- World Trade Organization, ‘Appellate Body Repertory of Reports and Awards 1995-2013 – Interpretation’ https://www.wto.org/ english/tratop_e/dispu_e/repertory_e/i3_e.htm accessed 30 November 2022.

- Ibid.

- Christian Tomuschat, ‘International Law: Ensuring the Survival of Mankind on the Eve of a New Century General Course on Public International Law (Volume 281)’, Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law (Brill 1999) https://referenceworks

- But see already Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Bedingungen des Friedens, Friedenspreis des deutschen Buchhandels, https:// friedenspreis-des-deutschen-buchhandels.de/fileadmin/user_upload/preistraeger/reden_1950-1999/1963_v_weizsaecker.pdf

- Craig VanGrasstek, The History and Future of the World Trade Organization (World Trade Organization 2013). See also Terence P Stewart, The GATT Uruguay Round: A Negotiating History (1986-1992) (Kluwer Law and Taxation Publishers 1993).

- Markus Wagner, Article III of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, in: Laura Wanner, Peter-Tobias Stoll and Holger Hestermeyer (eds), Commentaries on World Trade Law: Volume 1 – Institutions and Dispute Settlement, 2nd ed., Brill 2022, 29, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=3676816

- Kyle Bagwell and Robert Staiger, ‘The WTO: Theory and Practice’ (National Bureau of Economic Research 2009, Working Paper 15445), www.nber.org/papers/w15445.pdf accessed 30 November 2022.

- Lisa Toohey and others, Weaponised Trade: Mapping the Issues for Australia (2022) 12, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4154030 accessed 8 September 2022.

- Ibid 27.

- William Hauk, ‘George W. Bush Tried Steel Tariffs. It Didn’t Work’ (The Conversation), https://theconversation.com/george-w-bush- tried-steel-tariffs-it-didnt-work-92904 accessed 30 November 2022.

- Mark Tran, ‘EU Plans Retaliation for Us Steel Tariffs’ The Guardian (22 March 2002), https://theguardian.com/world/2002/mar/22/ usa.eu accessed 30 November 2022

- Ibid.

- Joseph Francois and Laura Baugham, ‘The Unintended Consequences of U.S. Steel Import Tariffs: A Quantification of the Impact During 2002’ (2003), https://tradepartnership.com/pdf_files/2002jobstudy.pdf accessed 30 November 2022

- For a timeline of the trade war between the US and China, see Chad Bown and Melina Kolb, ‘Trump’s Trade War Timeline: An Up-to- Date Guide’ (Trump’s Trade War Timeline: An Up-to-Date Guide, 16 April 2018), https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment- policy-watch/trumps-trade-war-timeline-date-guide accessed 30 November 2022.

- Tolulope Anthony Adekola, ‘US–China Trade War and the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism’ (2019) 18 Journal of International Trade Law and Policy 125, 127.

- Chad Bown and Melina Kolb (n 15).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- United States Department of Commerce – Bureau of Industry and Security, Implementation of Additional Export Controls: Certain Advanced Computing and Semiconductor Manufacturing Items; Supercomputer and Semiconductor End Use; Entity List Modification, Docket No. 220930-0204, https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2022-21658.pdf accessed 30 November 2022.

- Gregory C. Allen Choking Off China’s Access to the Future of AI, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 2022, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/221011_Allen_China_AccesstoAI. pdf?TMRG1RYN1EZyPhrrxoU7s2VzCs4Tjr4Q

- Weihuan Zhou and James Laurenceson, ‘Demystifying Australia – China Trade Tensions’ [2021] SSRN Electronic Journal 2, https:// ssrn.com/abstract=3806162 accessed 8 September 2022

- ‘China Is Curbing Imports of More and More Australian Goods’ The Economist, https://economist.com/asia/2020/11/12/china-is- curbing-imports-of-more-and-more-australian-goods accessed 30 November 2022

- Markus Wagner and Weihuan Zhou, ‘It’s Hard to Tell Why China Is Targeting Australian Wine. There Are Two Possibilities’ (The Conversation), https://theconversation.com/its-hard-to-tell-why-china-is-targeting-australian-wine-there-are-two-possibilities-144734 accessed 8 September 2022. See also Trish Gleeson, Donkor Addai and Liangyue Cao, ‘Australian Wine in China: Impact of China’s Anti-Dumping Duties’ (ABARES Research Report 21.10, July 2021).

- Zhou and Laurenceson (n 20) 19.

- Ibid 9.

- Ibid.

- Ibid 10.

- Ibid.

- Jonathan Galloway, Kearsley, Eryk, and Bagshaw, Anthony, ‘“If You Make China the Enemy, China Will Be the Enemy”: Beijing’s Fresh Threat to Australia’ (The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 November 2020), https://www.smh.com.au/world/asia/if-you-make-china-the- enemy-china-will-be-the-enemy-beijing-s-fresh-threat-to-australia-20201118-p56fqs.html accessed 30 November 2022.

- Markus Wagner and Weihuan Zhou, ‘It’s Hard to Tell Why China Is Targeting Australian Wine. There Are Two Possibilities’ (The Conversation), https://theconversation.com/its-hard-to-tell-why-china-is-targeting-australian-wine-there-are-two- possibilities-144734 accessed 8 September 2022

- Lisa Toohey, Markus Wagner and Weihuan Zhou, ‘A Road to Rapprochement for Australia–China Relations’ (East Asia Forum, 5 July 2022), https://eastasiaforum.org/2022/07/05/a-road-to-rapprochement-for-australia-china-relations accessed 30 November 2022.

- Matthew Crowe and Knott, David, ‘Xi Jinping Meets with Anthony Albanese, Ending Diplomatic Deep Freeze’ (The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 November 2022), https://smh.com.au/politics/federal/xi-jinping-meets-with-albanese-ending-diplomatic-deep-freeze- 20221115-p5byhb.html accessed 30 November 2022.

- Lowy Institute, ‘China: Economic Partner or Security Threat – Lowy Institute Poll’ (Lowy Institute Poll 2022), https://poll. lowyinstitute.org/charts/china-economic-partner-or-security-threat accessed 30 November 2022.

- Andrew Forrest, ‘Who Cares About the Australia-China Relationship?’ (The Interpreter), https://lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/ who-cares-about-australia-china-relationship accessed 30 November 202.

- Bonnie Girard, ‘China, US Woo Pacific Island Nations’, https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/china-us-woo-pacific-island-nations accessed 30 November 2022.

- Jon Henley, ‘Is Europe’s Gas Supply Threatened by the Ukraine Crisis?’ The Guardian (3 March 2014), https://theguardian.com/ world/2014/mar/03/europes-gas-supply-ukraine-crisis-russsia-pipelines accessed 30 November 2022.

- Andrew Gardner, ‘Ukraine Signs Landmark Eu Deal’ (POLITICO, 21 March 2014), https://politico.eu/article/ukraine-signs-landmark- eu-deal accessed 30 November 2022.

- Euronews, ‘Russia Is Using Gas as “Weapon of War,” Says French Ecology Minister’ (euronews, 30 August 2022), https://euronews. com/my-europe/2022/08/30/russia-is-using-gas-as-weapon-of-war-says-french-ecology-minister accessed 30 November 2022.

- European Council – Council of the European Union, ‘Energy Prices and Security of Supply’ (30 November 2022), https://consilium. europa.eu/en/policies/energy-prices-and-security-of-supply accessed 30 November 2022.

- Raphael Cohen and Andrew Radin, Russia’s Hostile Measures in Europe: Understanding the Threat (RAND Corporation 2019) https://rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1793.html accessed 30 November 2022; Luigi Scazzieri, ‘Have We Passed the High- Water Mark of European Unity on Ukraine?’ (EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, 15 June 2022), https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/ europpblog/2022/06/15/have-we-passed-the-high-water-mark-of-european-unity-on-ukraine accessed 30 November 2022..

- Michael Smith and Hans van Leeuwen, ‘Lithuania Shows the World China’s “Nuclear Option” on Trade’ (Australian Financial Review, 9 December 2021), https://afr.com/world/asia/lithuania-shows-the-world-china-s-nuclear-option-on-trade-20211208-p59g0n accessed 30 November 2022.

- World Trade Organization, DS610: China – Measures Concerning Trade in Goods and Services (26 April 2022), https://wto.org/ english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds610_e.html

- Henry Farrell and Abraham L Newman, ‘Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion’ (2019) 44 International Security 42.

- Brian Deese, ‘Remarks on Executing a Modern American Industrial Strategy by NEC Director Brian Deese’ (The White House, 13 October 2022), https://whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/10/13/remarks-on-executing-a-modern-american-industrial-strategy-by-nec-director-brian-deese accessed 30 November 2022.