by Eva U Wagner

New Zealand “Back on Track”?

#9/23

23 October 2023

New Zealand has held general elections on 14 October. According to the preliminary election result, the centre-right party has achieved 39% of all “ordinary” votes, (50 seats – 17 more than 2020), followed by the Labour Party with 27% (34 seats – 31 less than 2020), the Green Party with 11% (14 seats – 4 more than 2020), the ACT Party with 9% (11 seats – 1 seat more than 2020), the NZ First Party with 6.5% (8 seats – 8 more than 2020 as the party back then did not meet the 5% threshold) and the Maori Party with 2.6% (4 seats – 2 more than in the last election). The voter turnout is estimated at about 78% (compared to about 82% in 2020). Voters abroad could cast their vote since 27 September; voters in the country could cast their vote since 2 October – about 1.15 million voters made use of this option (compared to about 1.98 million in 2020 and about 1.24 million in 2017). Notably, the so called “special votes” (including overseas votes) are estimated at 567,000 (20.2% of all votes) (compared to 504,621 in the last election), with the overseas votes estimated around 80,000.

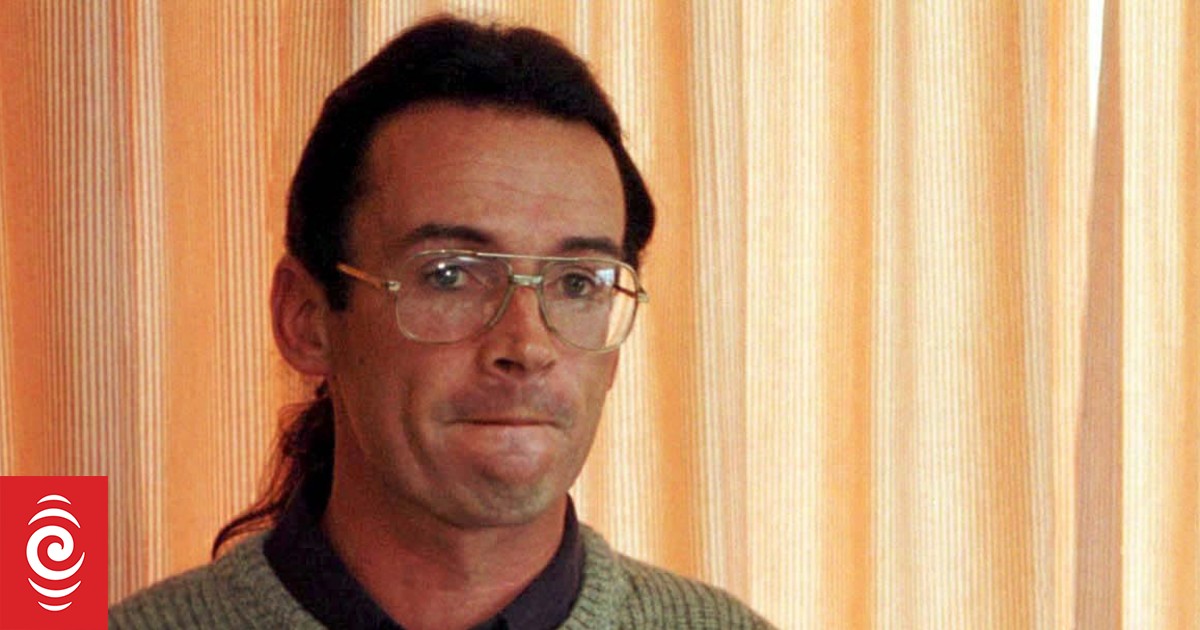

If this were to be the final election result, there would be 121 seats in parliament, including one overhang seat. This, in turn, would mean that the National Party could govern in coalition with its traditional coalition partner, the ACT Party (evolved from the Association of Consumers and Taxpayers), led by David Seymour. There are 2 factors that could change the final election result. First, the “special votes” could make a difference, at least if most overseas voters had voted again as they usually do, namely for Labour or another party from the left spectrum of politics. Given that many of the overseas voters would have been locked out of the country during the pandemic, they might however have opted to give their vote to another party this time. Secondly, following the death of one of the candidates (Neil Christensen from the ACT Party), a by-election has been scheduled for the electorate of Port Waikato. If the National Party were to lose a seat, or if there were to be an additional overhang seat, the party would additionally depend on the support of the New Zealand First Party, led by Winston Peters. Accordingly, National Party leader Luxon has commenced coalition negotiations with both parties.

What does this mean for New Zealand?

According to the National Party’s election slogan, the party aims to bring New Zealand “back on track”. What this means may be taken from Mr Luxon’s election campaign speech, in which he promised that his party if elected would

- Fix the economy (by lowering inflation and growing the economy)

- Finance – Implement tax cuts

- Infrastructure – Build infrastructure through its Roads of National Significance policy

- Legal system – Restore law & order (eg by introducing boot camps for serious young offenders and stronger sentencing)

- Education – Lift school achievement through an enforced hour of reading, writing and maths, alongside banning mobile phones and regular assessment)

- Health – Cut health waiting times by training more health workforce

- Seniors – Support through the Winter Energy Payment and increasing Super every year

- Environment – Net zero emissions by 2050

The ACT Party wants the “change of government to be a government of change” and aims to

- Slash wasteful government spending

- Enforce consequences for criminals

- End divisive race-based policies

The election campaign of all parties was dominated by domestic topics, including the economic recovery from the pandemic and the cyclone that hit hard the North Island earlier this year. Of all domestic issues, there is one that sticks out from an outsider’s viewpoint: The Treaty of Waitangi, the question of its interpretation, and thus the role of Maori in the country. New Zealand has a population of about 5 million people, including about 17% Maori (compared to 3.8% indigenous people in Australia). Next to English, Maori is one of 3 official languages (with sign language being the third official language). There are 2 language versions of the Treaty. In the English version, the Maori give the British Crown ‘absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of sovereignty’ over their lands but are guaranteed ‘undisturbed possession’ of their lands, forests, fisheries, and other properties. Interestingly, the wording seems to bear resemblance to the relationship in the German legal system between the owner (Eigentümer) and the tenant (Mieter) of rental property. In the Maori version of the Treaty, the Maori give the Crown ‘kawanatanga katoa’ – complete governorship. And they are guaranteed ‘tino rangatiratanga’ which translates into self-governance or the unqualified exercise of chieftainship over their lands, dwelling places, and all other possessions.

There are calls for the principles of the Treaty to be implemented into legislation. Likewise, there are calls for the country to be renamed into “Aotearoa” (land of the long white cloud), or at least for its Maori name to be added to the official English name. The Supreme Court of New Zealand has recently confirmed the relevance of Maori law (tikanga) to the country’s legal framework (Peter Ellis case). The country’s tertiary education sector, more precisely, the law schools, must soon include Maori law with their curricula. These measures, alongside the concept of called co-governance (eg Waikato River Authority) and the priority given to Maori (and Pasifika) people in the health system (at least in Auckland with a population of 2 million, including a Pacific diaspora of about 200,000), are debated controversially. The National Party leader has made it clear that he would not generally oppose a referendum on the Treaty of Waitangi. On the other hand, Luxon left no doubt that he was opposed to co-governance, a separate Maori health authority and that priority be given in the health system to one ethnic group of the population, saying he would make decisions on the basis of the national good rather than on ethnic grounds.

In terms of foreign policy, the new government will have to decide on the continued support of Ukraine, its approach to the conflict between Israel and Palestine and, most likely, the question of whether to join the so called “second pillar” of the AUKUS Partnership Agreement entered between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the USA. This pillar involves the sharing of information in new cutting-edge defence technologies such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing and cyber capabilities. New Zealand is already a member of the Five Eyes intelligence network, joining AUKUS would mean an even greater integration in this space but could potentially jeopardise its relationship with the (nuclear free) Pacific region.

The final election results will be released on 3 November.