by Eva U Wagner

Pacific Leaders United in Diversity

#12/23

27 November 2023

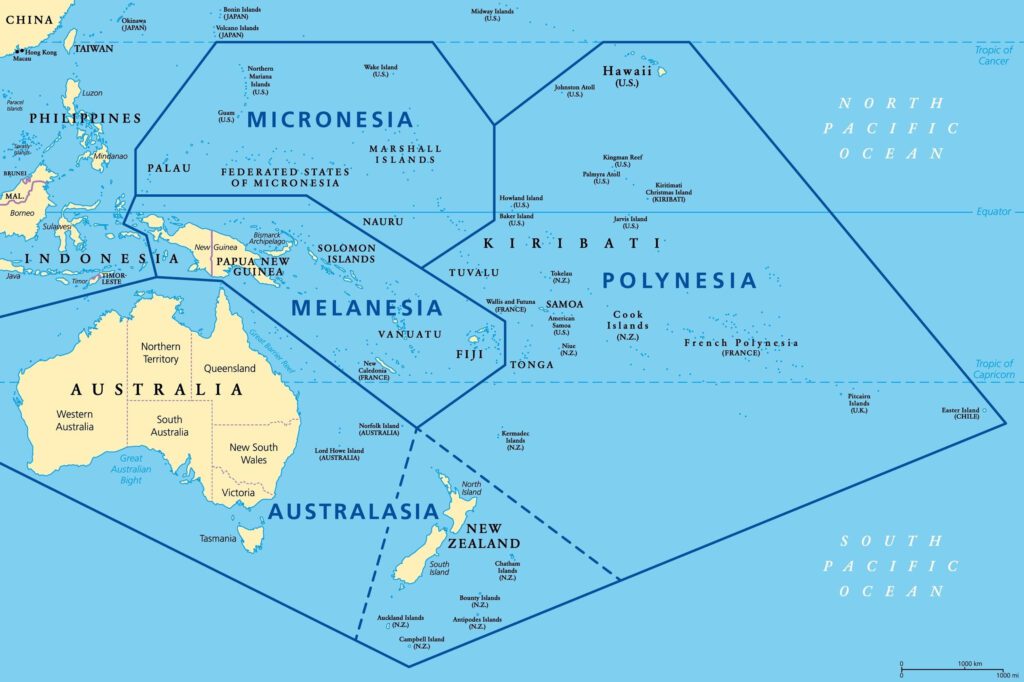

The 52nd Pacific Islands Forum 2023 (PIFLM52) was themed “Our Voices, Our Choices, Our Pacific Way: Promote, Partner, Prosper” and comprised two sessions: the Plenary, held on 8 November at the National Auditorium – Te A’re Karioi Nui in Rarotonga, and the Forum Leaders’ Retreat, held on board the Vaka Teariki Moana in Aitutaki on 9 November. The Forum was attended by the leaders of Australia, the Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Kiribati, Nauru, New Caledonia, Niue, Palau, Samoa, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Tonga, and Tuvalu. New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu were represented at Ministerial level. More precisely, New Zealand was represented by caretaker Deputy Prime Minister Carmel Sepuloni, accompanied by Government-elect representative the Hon Gerry Brownlee; the incoming prime minister and National Party leader, Christopher Luxon, was tied up with coalition negotiations after the country held general elections on 14 October. The Solomon Islands were represented by a delegation led by Foreign Minister Jeremiah Manele; Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare was purportedly attending to his duties as Minister for Pacific Games. The Prime Minister Prime Minister of Vanuatu, Charlot Sawai, was reportedly focussing on the country’s response to cyclone Lola, which made landfall on 25 October and has inflicted significant damage on his electorate of Pentecost Island. The absence of three Melanesian leaders was seen by some as a challenge for regional unity amid competition for influence between China and the United States but did not prevent concrete outcomes in the end.

According to the Communique issued at the end of the Forum, the Leaders inter alia endorsed the 2023 to 2030 Implementation Plan (Annex A) for the 2050 Blue Pacific Strategy, which articulates specific goals, outcomes, and regional collective actions across each of the Strategy’s thematic areas, namely:

- Political Leadership and Regionalism

- People-Centred Development

- Peace and Security

- Resources and Economic Development

- Climate Change and Disasters

- Ocean and Environment

- Technology and Connectivity

In the view of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), “[t]he rollout of this implementation plan so quickly after the development of the initial strategy in 2022 points to a high level of consensus among PIF leaders on the urgency of actualising PIF priorities and in presenting in unison to external partners how to best engage the Pacific”.

The Communique also tells us that climate change remains on the top of the agenda of the Pacific leaders, who not only re-affirmed their commitment to the implementation of the Paris Agreement but also approved the Pacific Resilience Facility (PRF) (Annex B), a Pacific-owned and Pacific-led facility to facilitate resilience financing throughout the region. Saudi Arabia pledged USD 50 million to kickstart the facility, which we are told was largely born out of the need for flexible and rapid small to medium-sized social and community grants throughout the Pacific. The Leaders also agreed on the Pacific Regional Framework on Climate Mobility (Annex C), that is, a Pacific Partnership for Prosperity priority which aligns with the 2050 Strategy as well as the 2018 Boe Declaration on Regional Security. The Framework firmly acknowledges the Forum members’ fundamental priority to stay in place in their ancestral homes, including through land reclamation. It is said to be a global first, aiming to provide practical guidance to governments planning for and managing climate mobility, while also respecting members’ national laws and policies. Following the 2021 Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones, the Forum leaders adopted the 2023 Declaration-on-Statehood-and-Protections-of-Persons (Annex D) in an endeavour to secure legal certainty of the Blue Pacific in the face of the existential threat of climate change. They noted that the security and full realisation of the Blue Pacific was not only fundamental to securing the rights, entitlements, and interests of all states and peoples of the Blue Pacific, but also to the maintenance of global peace and security.

As far as deep sea mining is concerned, one could say that the Leaders “agreed to disagree” and endorsed the convention of a PIF Talanoa Dialogue on this topic in 2024. Whilst some Pacific Island states (including the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga) plan to mine the ocean for high value metals, others oppose deep sea mining (Fiji, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Micronesia, Samoa, New Zealand, and Vanuatu). The Prime Minister of the Cook Islands, Mark Brown, went as far as to offer his guests items of cultural and unique significance to the Cook Islands, such as a traditional tivaevae (quilt) and a traditional Vaka (canoe), holding a Cook Islands nodule. Already last year, the President of Palau, Surangel Whipps Jr, – backed by many international marine experts – started a petition for a 10-year moratorium. At a film screening held in the context of the Forum, President Whipps Jr said that one of his biggest concerns was that the carbon released by the mining could result in the loss of species. He went on to say that the Pacific Islands shared one ocean and that something done in one part could affect all of them. The moratorium, he said, was meant to allow for the proper research to be done and to prevent the destruction of something that could never be brought back. Many larger industrial nations (including Germany, France and Canada) have joined the call for a moratorium.

In line with the Suva Agreement (concluded to reverse the so called “Micronexit”), the Forum leaders formally selected Nauru’s former president Baron Waqa as the next secretary general of the Pacific Islands Forum. This means Waqa would take office once the incumbent Secretary General, Henry Puna, from the Cook Islands, steps down next year. The President of Nauru, David Adeang, walked out of the Plenary meeting when his country’s controversial choice was raised. He and Mr Waqa are said to be linked to an Australian Federal Police corruption probe into the phosphate dealer Getax. The allegation is that the two of them accepted funding from the company. They are also said to have been instrumental in the sacking of the country’s (Australian) judiciary in 2014, and to have restricted media freedom in their country. As a result, critics deem Baron Waqa to be unfit to lead the Forum.

Other matters debated at the Forum included AUKUS (Leaders noted the update provided by Australia, welcomed the transparency of Australia’s efforts and commitment to comply with international law, in particular the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the Rarotonga Treaty, and IAEA safeguard agreements), and Fiji’s presentation on the concept of a zone of peace in the Pacific region. In a separate Statement on the Fukushima ALPS-Treated Nuclear Wastewater Issue, Forum leaders re-affirmed their concerns about the matter. Japan already released the third batch of contaminated water in the beginning of the month. In the absence of any alternative action available to them, the Leaders acknowledged the ongoing dialogue with Japan and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and announced further discussions in the next year. The Communique outlines further outcomes the discussion of which would exceed the scope of this Snapshot, so you it is suggested that you refer to the document and below links for further details.

Australia (together with Tuvalu) arguably made the most significant announcement at the sidelines of the Forum. More precisely, the Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his Tuvaluan counterpart, Kausea Natano, announced that their countries would upgrade their bilateral relations on the basis of the so called “Falepili Union” (a Tuvaluan word for the traditional values of good neighbourliness, care and mutual respect). The Union comprises a bilateral treaty between Tuvalu and Australia, and a commitment articulated in a joint leaders’ statement to uplift our broader bilateral partnership. One of the key elements of the Falepili Union Treaty provides for Australia to arrange for a “special human mobility pathway for citizens of Tuvalu to access Australia which shall enable citizens of Tuvalu to live, study and work in Australia, and to access Australian education, health and key income and family support on arrival” (Article 3(1)). In other words, Australia has agreed to accept climate change refugees from Tuvalu, half of whose capital Funafuti is estimated to be flooded daily by tidal waters by 2050. The deal was struck after Tuvalu approached Australia for assistance and is (at least initially) restricted to 280 Tuvaluan citizens per year to prevent “brain drain”. At this rate, it would take around 40 years for all Tuvaluan citizens to relocate to Australia.

Article 3: Human mobility with dignity

- Australia shall arrange for a special human mobility pathway for citizens of Tuvalu to access Australia which shall enable citizens of Tuvalu to:

- live, study and work in Australia;

- access Australian education, health, and key income and family support on arrival.

- To support the implementation of the pathway, Tuvalu shall ensure that its immigration, passport, citizenship and border controls are robust and meet international standards for integrity and security and are compatible with and accessible to Australia.

- Australia shall provide assistance to Tuvalu to enable it to meet its obligations under paragraph 2 of this article.

Further, the Treaty stipulates that “Australia shall, in accordance with its international law obligations, international commitments, domestic processes and capacity, and following a request from Tuvalu [emphasis added], provide assistance to Tuvaluan response to a major natural disaster, public health emergency of international concern [in other words, pandemics], and military aggression against Tuvalu (see Article 4(1)). In return, Tuvalu shall “mutually agree with Australia any partnership, arrangement or engagement with any other State or entity on security and defence-related matters. Such matters include but are not limited to defence, policing, border protection, cyber security and critical infrastructure, including ports, telecommunications and energy infrastructure” (Article 4(4)).

Article 4: Cooperation for security and stability

- Australia shall, in accordance with its international law obligations, international commitments, domestic processes and capacity, and following a request from Tuvalu, provide assistance to Tuvalu[i]n (sic) response to:

- a major natural disaster;

- a public health emergency of international concern;

- military aggression against Tuvalu.

- The Parties shall enter into an instrument to set out the conditions and timeframes applicable to Australian personnel operating in Tuvalu’s territory.

- In addition to the Parties’ rights and freedoms under international law, provided that advance notice is given by Australia, Tuvalu shall provide Australia rights to access, presence within, and overflight of Tuvalu’s territory, if the activities are necessary for the provision of assistance requested by Tuvalu under this agreement.

- Tuvalu shall mutually agree with Australia any partnership, arrangement or engagement with any other State or entity on security and defence-related matters. Such matters include but are not limited to defence, policing, border protection, cyber security and critical infrastructure, including ports, telecommunications and energy infrastructure.

Supporters of the Treaty point out that the agreement provides Tuvaluan citizens with a home as the rising sea level renders their own uninhabitable. The Union, they say, would be another step towards a visa-free Pacific region. Others criticise the Treaty for being neocolonialistic, saying that Australia was merely pursuing its own security interests in the region. Tuvalu is of course one of the four remaining Pacific Island states that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan. By having a say in regards to Tuvalu’s external security and defence relations, Australia can in theory prevent the country from entering into such arrangements with China. There was speculation that Kiribati and Nauru – two other low lying Pacific countries – might enter into similar agreements with Australia in the future. Media report that Foreign Minister Penny Wong left the door open for it, suggesting the Falepili Union could serve as a model: “[t]hat’s a matter for those nations but I think what this does signal is how we are prepared to approach our membership of the Pacific family”. Kiribati’s President Taneti Maamau told the media that the agreement would help Australia “look after” Tuvalu’s development needs, and potentially its security needs as well. “It’s an important initiative for Australia to take, and I congratulate Australia on taking it,” he said. When asked if he would be open to a similar pact with Australia, however, he was reportedly non-committal saying “maybe, but we have our own strategies … our own initiatives … and our own way of doing things”. Maamau also said that Australia had no yet approached Kiribati in this regard. His statement (and that of FM Wong) contradicts rumours according to which Australia had approached Kiribati, and that the country was prevented from entering into such an agreement because of prior commitments to China.

In sum, PIFLM52 proved that the Pacific Island states can be “united in diversity” – something they have in common with the European Union, whose motto it is.

The 53rd PIF Leaders Meeting is scheduled to be held in August in Tonga next year. The 54th PIF Leaders Meeting is scheduled to be held in the Solomon Islands in 2025.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/QUFJOGSWYVM7LMYHRGEMNGYNGM.jpg)

Further readings – Samoa Agreement:

Further readings – Pacific Games: