Digital Snapshot

by Sophia Brook

Understanding the AUKUS Submarine Deal

#4/23

17 March 2023

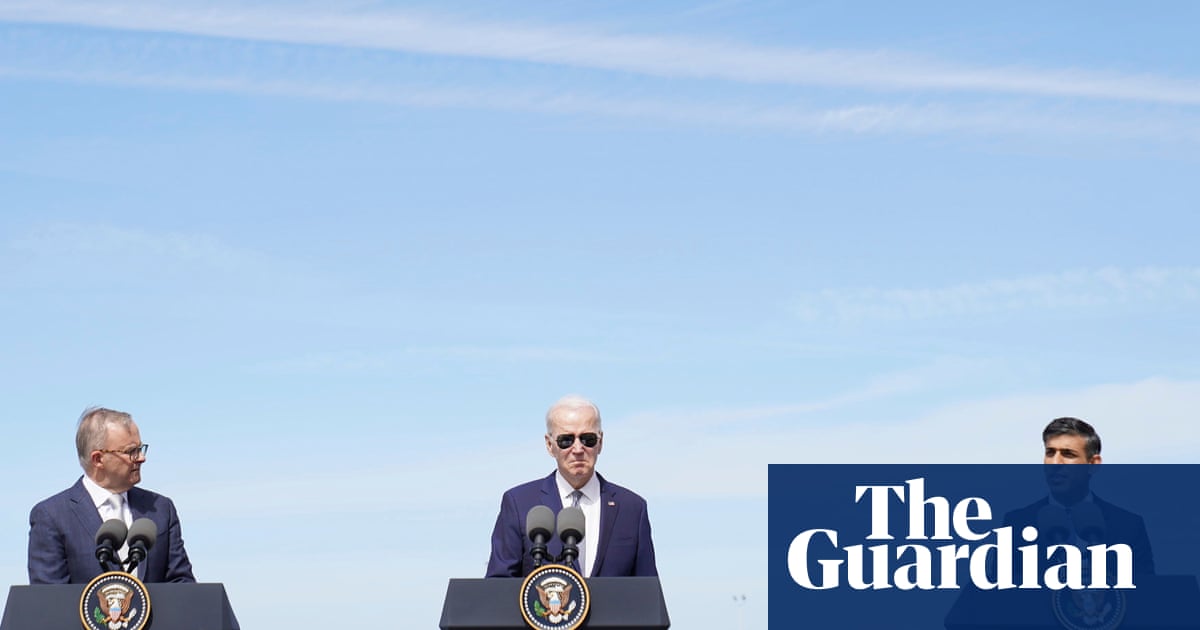

In a joint statement this week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, US President Joe Biden and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak officially announced the pathway to achieving the first major initiative promised under the 2021 AUKUS deal, Australia acquiring conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs).

The overall goal is for Australia to end up with three US Virginia-class submarines (with the option to buy two additional ones) and eight of the entirely new SSN-AUKUS submarines, meaning a total of 11, potentially 13, submarines. With the whole process to be completed in the 2060s.

The SSN-AUKUS is a new type of nuclear submarine, based on a British design combined with either US technology or a US combat system.

The pathway to achieving this goal is comprised of four main steps:

From 2023, Australian military and civilian personnel will be embedded in the US and Royal Navies and submarine industrial bases. PM Albanese confirmed that this was already happening in order to build up Australia’s knowledge in this area and start training personnel. At the same time, the US would start increasing ‘SSN port visits to Australia […] with Australian sailors joining U.S. crews for training and development’. The UK also intends to increase visits, however, this will not happen before 2026.

From 2027, both the US and the UK will ‘begin forward rotations of SSNs to Australia to accelerate the development of the Australian naval personnel, workforce, infrastructure and regulatory system necessary to establish a sovereign SSN capability’.

From the early 2030s, Australia will be able to buy three US Virginia-class submarines to bridge its capability gap until the completion of the new SSN-AUKUS, with the option to buy two more submarines if required. This part of the plan still needs to be approved by the US Congress, which could pose a potential stumbling block depending on US politics at the time.

From the late 2030s, the UK intends to deliver the first SSN-AUKUS submarine to its own Royal Navy, while Australia plans to provide the first Australian-built SSN-AUKUS to its navy in the early 2040s. As expected, the Albanese government designated South Australia as its main future submarine industry hub.

According to this timeline, Australia should receive five of the eight SSN-AUKUS submarines by the mid-2050s and the remaining three in the 2060s, with ‘one submarine built every two years from the early 2040s’.

The Australian government expects that this plan will present ‘a whole of nation opportunity; for new jobs, new industries, and new expertise in science, technology, and cyber’, with ‘$6 billion invested in Australia’s industrial capability and workforce over the next four years, creating around 20,000 direct jobs over the next 30 years’. The gradual build-up hereby is designed to assist Australia to develop its industrial capacities over time, so that the SSNs will become a ‘sovereign’ Australian capacity. This aspect in particular raised concerns in the lead-up to the announcement, with experts worrying that Australia might become so dependent on US and UK expertise that it would lose its sovereignty in defence matters.

Despite these efforts to build up Australian know-how, experts are still worrying that, with Australian ports becoming frequent hubs for US submarines, Australia might be forced or at least expected to stand ready to support any US initiative in the region should it come to a conflict with China over Taiwan in the future.

In addition to this, several other concerns have been raised by experts post reveal. Firstly, according to government estimates, the ‘cost of acquiring, building and sustaining the submarines is expected to be between $268 billion and $368 billion by 2055’. In comparison, Australia originally estimated it would cost $225 billion to build and sustain the 12 French submarines. With a price tag like this, the AUKUS pact could potentially become a burden to future governments, even though both sides of politics currently pledge support for the plans.

Secondly, defence experts have warned that Australia and the UK might have difficulties recruiting and training enough skilled workers to build the SSNs, with some speculating that the UK and Australia might need to ‘alternate parts of the production process, so that the relevant workers could rotate between the Cumbrian and South Australian shipyards’.

Thirdly, the successful outcome of the initiative is now dependent on ‘the whims of three governments’, with the main question being whether AUKUS will survive a US government change or, in the worst case, another Trump-esque presidency.

Fourthly, with a rise in detection technology, some experts raised the concern that by the time the submarines are built, their stealth-capacity will have become obsolete.

Lastly, Australia will have to carefully manage the concerns regarding its adherence to the NPT voiced by some of its closest neighbouring states, most notably Indonesia. The Indonesian Foreign Minister stating that ‘maintaining peace and stability in the region is the responsibility of all countries. […] Indonesia expects Australia to remain consistent in fulfilling its obligations under the NPT and IAEA safeguards, as well as to develop with the IAEA a verification mechanism that is effective, transparent and non-discriminatory’. According to some media reports, a senior Indonesian official further stated that ‘the country’s sea lanes should not be used by Australian nuclear-propelled submarines because “AUKUS was created for fighting”’. Needless to say that Chinese officials have already reiterated their criticism of the deal, but, so far, they have not received the support they might have expected.

Regardless of the aforementioned concerns and criticisms, acquiring US Virginia-class submarines and the SSN capability, once established, will be valuable assets in Australia’s defence arsenal. Not only will Australia gain access to advanced US and UK technical know-how, it will also ‘open up opportunities for advanced undersea operations’.

The AUKUS deal also offers a positive outlook for the region. Some experts have noted that the announced plans could indeed ‘foster an Indo-Pacific that is “open, stable, prosperous and respectful of sovereignty, human rights and international law”’, as the timeline lays the ‘foundations for a partnership that will last at least 50 years’, not only binding the US, UK and Australia together but also ‘binding them to the Indo-Pacific’.

Joint Leaders Statement On AUKUS | Prime Minister of Australia

AUKUS Remarks | Prime Minister of Australia

AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine pathway | Defence Ministers

Today’s significant AUKUS announcement about Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines is the single biggest investment in our defence capability in our history and represents a transformational moment for our nation, our Defence Force and our economy.

AUKUS submarine workforce and industry strategy | Defence Ministers

The Albanese Government is developing a comprehensive AUKUS Submarine Workforce and Industry Strategy to support delivery of advanced conventionally-armed nuclear-powered submarines to the Australian Defence Force.

https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2023-03-14/aukus-nuclear-powered-submarine-pathway

https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2023-03-14/aukus-submarine-workforce-and-industry-strategy

When are we getting nuclear submarines? Here are the details of the AUKUS plan

The final details of Australia’s first nuclear submarine fleet have been unveiled — along with the price tag. Here’s the plan and when we might see them in the water.

Eight submarines, three decades, up to $368 billion: Australia’s historic AUKUS plan at a glance

Australia has now outlined its plan to acquire nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS agreement with Britain and the United States. This is how it will be done.

What is the Aukus submarine deal and what does it mean? – the key facts

The four-phase plan has made nuclear arms control experts nervous … here’s why

Australian SSNs will open up opportunities for advanced undersea operations | The Strategist

The announcement of the agreed pathway for Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) under the AUKUS deal provides clarity about how and when Australia will have this important capability. The process begins with an increased…

What a $368 billion submarine price tag means for the budget

The price of nuclear-powered submarines is striking. But there are bigger, faster-growing costs that could leave the budget in the red.

‘We need to respond’: Mammoth submarine outlay sparks budget battle

The government says the AUKUS investment is essential to shield Australia from threats, but the potential $368 billion cost sets up a long political fight.

No briefing required: China already knows AUKUS is about them. So what happens next?

From a dalliance with Japan, to an extended French flirt, Australia’s now firmly back in the bosom of its Anglosphere allies during a meandering and disjointed journey to find its next generation submarine fleet and with that, Australia’s nuclear age has begun, writes Andrew Probyn.

Nuclear submarines needed as region has become ‘less stable’, AUKUS task force head says

The head of Australia’s AUKUS task force says China’s military expansion justifies the purchase of new nuclear-powered submarines, while reassuring Australians the nuclear reactors on board the vessels will be safe.

What these six words in Joe Biden’s AUKUS speech told us about his next political battle

Unlike Anthony Albanese, who has shaken hands on the AUKUS deal originally struck by his predecessor, Joe Biden has the responsibility of setting up the project in a way that convinces those who come after him to see it through, writes Carrington Clarke.

Could a Donald Trump-shaped torpedo sink Australia’s $368bn Aukus submarine plans?

Technical risks abound in multi-decade plan for Australia to obtain nuclear-powered submarines. There are plenty of political ones, too

Australia has to dispose of nuclear waste under the AUKUS submarines deal. Will this be in breach of a treaty?

As part of the AUKUS deal, Australia must manage all radioactive waste generated by the submarines on Australian soil. What are the types of waste and where will it be disposed of?

Experts pinpoint top AUKUS headache – and it’s not money

Analysts warn that Britain and Australia may need to in effect alternate the production of the subs if there are not enough workers to go around.

AUKUS submarines a question mark for adversaries – and for Australians

Is this the real deal or merely the fourth edition of Australia’s traditional game of “Fantasy Subs”?

The weak points that make AUKUS a $368b gamble

Anthony Albanese has gone all in on a historic deal to get nuclear-powered submarines for Australia. Much of the plan is logical, but it has some weaknesses.

Navy chief embarks on SE Asia tour to soothe concerns about subs deal

Vice Admiral Mark Hammond will meet with Indonesia’s navy chief, Admiral Muhammad Ali, next week with AUKUS set to be a permanent thorn in the bilateral relationship.

AUKUS binds Britain to Australia and a free and open Indo-Pacific | The Strategist

It’s been a big day for Australia–UK relations. Sandwiched between the release of the ‘refresh’ of the integrated review in London and the AUKUS submarine announcement in San Diego, a bilateral partnership growing in warmth…

With AUKUS, Australia has wedded itself to a risky US policy on China – and turned a deaf ear to the region

Labor has touted a renewed engagement with the Asia-Pacific since coming to power. The submarine deal, however, is not in this spirit.

‘AUKUS created for fighting’: Push for Indonesia to refuse access to subs

Indonesia is concerned Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines could instigate a regional arms race that would heighten tensions.

Australia signs up for the United States’ arms race with China

Australia has tied its colours to America’s increasingly hawkish mast as the superpower navigates the choppy waters of the Indo-Pacific.

US and UK jump-start Australia’s nuclear submarine program | The Strategist

Australia’s nuclear-powered, conventionally armed submarines will be of a new British design, but their reactors, combat systems and heavyweight torpedoes will all be American. After 18 months of intense consultations, details of this massive joint…

AUKUS submarines will strengthen Australia’s sovereignty | The Strategist

The formal unveiling of the AUKUS plan is still a few days away, but we are already seeing strong signs that it will constitute a genuine trilateral partnership. If the blizzard of news reports detailing the plan is…

AUKUS: Many questions, revealing answers

What Lowy Institute’s analysts have so far made of the nuclear-powered submarine announcement.

Progress in detection tech could render submarines useless by the 2050s. What does it mean for the AUKUS pact?

The first AUKUS-class submarine will be delivered in the 2040s. We may only get about a decade of use before adversaries can easily detect the new boats.

AUKUS submarine plan will be the biggest defence scheme in Australian history. So how will it work?

The plan will see Australia supplied with nuclear-propulsion submarines more than a decade earlier than preciously envisaged.

China says Aukus submarines deal embarks on ‘path of error and danger’

Beijing accuses US, UK and Australia of disregarding global concerns with plan to build nuclear-powered vessels

China is turning to an unlikely place in its bid to thwart Australia’s AUKUS submarine deal

China is embarking on a diplomatic mission to torpedo Australia’s nuclear submarine program while ramping up its own arsenal, but the move appears to be driven by genuine fear over the real agenda behind AUKUS, writes Bill Birtles.

Beijing declines AUKUS briefing but no backlash emerges

China stands alone among more than 60 nations in refusing to be briefed by the Albanese government over the AUKUS security pact.

Penny Wong hits back at China’s claim Aukus nuclear submarines will fuel an arms race

Foreign minister set to visit south-east Asia and the Pacific to reassure countries Australia does not seek to escalate military tensions